Brexit and movement of people

by Alexandra Bosbeer

Spending this summer in the UK – especially for me, a non-UK EU citizen – has felt like a slightly risky direct experience of history. Reading national papers gives one a sense of the delicate selection of vocabulary in the multi-faceted discussion about what Brexit might mean. The desire for benefits without costs, does seem a bit idealistic. Yesterday, on 5 September, the Brexit minister was clear that there must be “controls on the numbers of people who come to Britain from Europe” even if that might mean less access to the single market. (This is followed within a day by the Prime Minister’s team’s statement that the single market remains an ideal.) And Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson had said only the day before, on 4 September, that the UK looks forward to welcoming more Polish immigrants.

Poland with more than 34 million people, is the 6th largest population among the 28 EU Member States. With the GDP per capita at a little more than a third of the EU average and 10% unemployment, one isn’t surprised that Polish people might seek work outside of Poland. In 2015, it was estimated that 831,000 Polish people lived in Britain. One doesn’t often see this debate set in context: that it was the UK national government’s own decision in 2004, to allow people from the new Member States immediate access to Britain, while most other EU countries first instigated a waiting period.

Changing the migration picture

Who is it exactly that the public imagine will be prevented from entering the UK after Brexit? Is it the 21.3 million refugees globally fleeing armed conflict? In 2015, a little over 32,000 people applied for asylum in Britain; the Red Cross says this number was about 38,000. Or migrants, who are seen as having more of a choice about their move. Are migrants always easy to distinguish from refugees, when poverty can be structural violence for marginalised groups, when wars might damage infrastructure which is not soon repaired, or climate change could be a main factor in a crop failure that causes starvation? Of course, it does not help clarity that the press of people trying to cross into Europe across the Mediterranean, is often called a migrant crisis.

In 2012, a poll showed half of the people in Britain believed that more than 1 in 10 people in Britain were refugees – although the British Red Cross states it is less than 0.2%

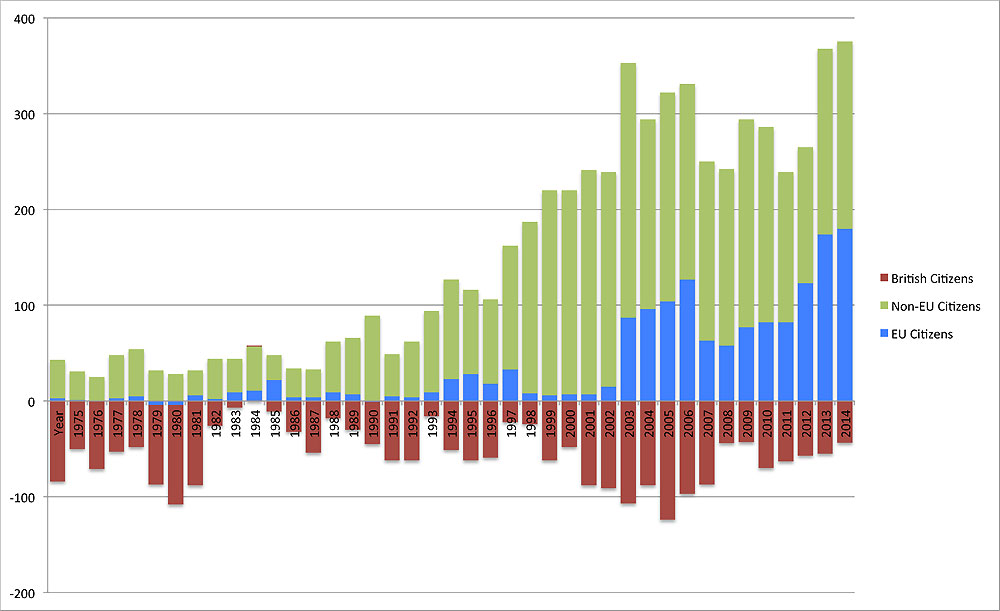

But of course one would need to be extremely callous to bar people in extreme need. Although there are more people arriving each year in Britain from non-EU countries, in this case the target group for reduction are the EU migrants.

The ‘other’

Why is immigration of other Europeans such a hot topic in Britain today? It seems that EU immigrants might be a fairly acceptable group of ‘other’. One hopes it would still be morally outrageous for a politician in the UK to focus on those non-EU migrants who are racially different from white English people (although a populist party in the Netherlands has done just that). The other Europeans who can be identified by language if not by skin colour, might be slightly more acceptable targets. So, for example, Nigel Farage almost sounds like an anti-racist in his recent post on the UK Independence Party (UKIP) website when he writes “Given that myself and others also campaigned for a migration system that would treat all who wanted to come equally, any preference for EU nationals would be totally unacceptable”. (I will leave aside the revisionist nature of a claim today of any coherent plan in the ‘Leave’ campaign.)

But populism needs an ‘other’ against which ‘the [pure, real, original] people’ can be contrasted. This dualistic approach prohibits the pluralism which is the reality – and richness – of all of our societies today. Populism focuses on a threat from which ‘the people’ must be protected. So, for example, numbers of foreigners in Britain cited by the ‘Leave’ campaign might have been ‘slightly’ inflated (by 3 million) during the pre-referendum campaign. Fear can easily escalate into violence: hate speech and hate crime. Harkening back to a past to which we can return if only the risk posed by the ‘other’ is removed, is backward-looking rather than forward-looking. And it can only be maintained through half-truths and oversimplifications, as UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein pointed out today in an excellent speech.

Fighting back with facts did not succeed in the immigration debate before the Brexit vote. Perhaps we must think more deeply, consider the anxiety and fear that underlies a person’s support for a populist. We know humans are not always logical, and we know that fear is a stronger motivator than logic. What can we do to overcome logical simplification and creation of fear? When we solve that problem, we may be able to develop pluralist society in which we are truly safe.